Search on Streetmap for “Hammer” and you’ll find well over 200 places, road names and streets bearing the name. Narrow the search to Haslemere and a pattern emerges: seven “Hammers”, five “Furnaces”, several “Mill Ponds”, “Pond Bays” and a “Minepit Copse”.

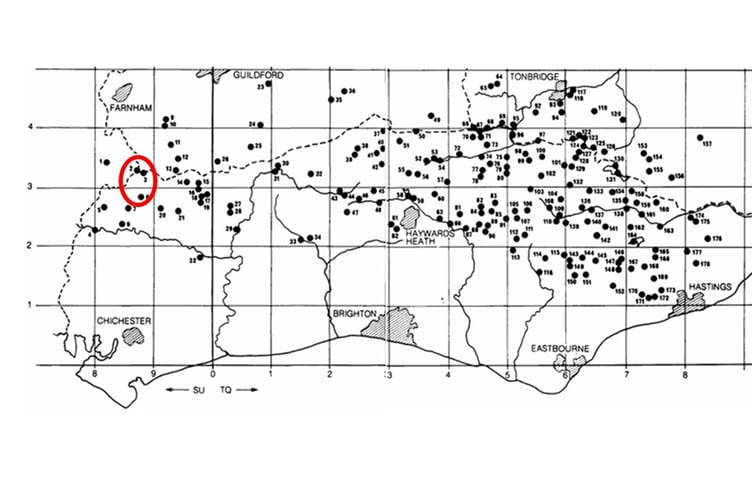

These are legacy reminders of one of the area’s defining industries: iron production — specifically the Wealden Iron industry. The Weald, a corner of South East England between the North and South Downs, once hosted more than 170 ironworking sites. Hammer Vale was on the westernmost edge.

Producing iron in Britain dates back 2,700 years to the beginning of the Iron Age (800 BC to AD 43), long before the Romans arrived. Ancient Britons had already learned to extract iron from ore and forge it into tools and weapons, replacing bronze — an alloy that required tin and copper. Iron was more durable and far more abundant in British soil.

In the earliest days, all that was needed was iron ore and wood (typically oak) to produce charcoal. The charcoal and ore were burned in a clay or stone vessel called a bloomery, about two metres high, with air fed by hand-operated bellows. The waste (slag) ran out the base; the remaining iron was hammered to remove impurities and turned into usable metal.

A major shift came in the 15th century with the arrival of the blast furnace from continental Europe. What had been a cottage industry became a continuous, large-scale process. Furnaces around eight metres tall ran 24 hours a day for months on end, producing up to a ton of iron a day — a massive leap from the handfuls produced in a bloomery.

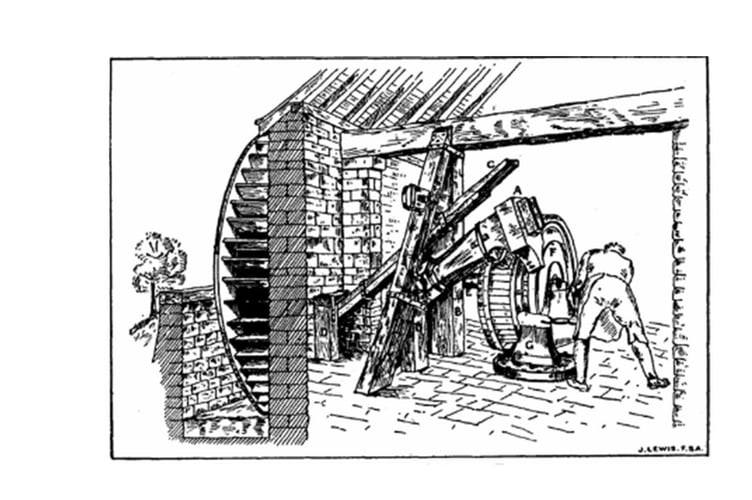

Hammer Vale wasn’t a furnace site — the nearest was at Fernhurst, where molten iron was cast into moulds. Cast iron was ideal for cannon but too brittle to be reworked. So bars were carted to Hammer Vale for refining into wrought iron — “wrought” being the old word for “worked”.

The site at Hammer Vale was known as a finery. There, cast iron was reheated and hammered — with the carbon content carefully reduced. The hammerman, or finer, judged when the iron was ready by the heat required to keep it molten. It was shaped into bars called anconies, with bulbous ends, ready to be turned into horseshoes, railings, or tack.

Two major factors brought the Wealden iron industry to an end. One was the soaring cost of charcoal, driven up by demand from other trades like glassmaking. But the final blow came with the discovery of coke — roasted coal — near Ironbridge, the cradle of the Industrial Revolution.

Coke was cheaper and more powerful than charcoal, and easier to mine. It fuelled larger, more efficient blast furnaces. The Weald couldn’t compete. Hammer Vale ceased operations in 1777; the final site in the region closed in 1827.

You can talk a walk through the iron industry’s local history yourself. Just head to the phone box or the Prince of Wales pub at Hammer Vale, and it’s just a five-minute walk to the site.

Exit the car park and turn left. Walk past the turning to Sandy Lane. A few metres further, cross the infant River Wey via the road bridge. Look immediately left for a signed footpath. A short way along you’ll come to the old sluice.

Look closely and you’ll see the stone slots where gates were raised and lowered to regulate the water flow that once powered the hammer. Rope grooves carved into the stone mark the passage of centuries.

To learn more, visit the Rural Life Centre near Tilford, where there’s a model of the Fernhurst Furnace: rural-life.org.uk. Or explore the real thing at fernhurstfurnace.co.uk — an open day is planned for September.

By Andy Jones

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.