On August 15, a poignant commemoration will take place, marking 80 years since the end of the Second World War in the East and the victory over Japan.

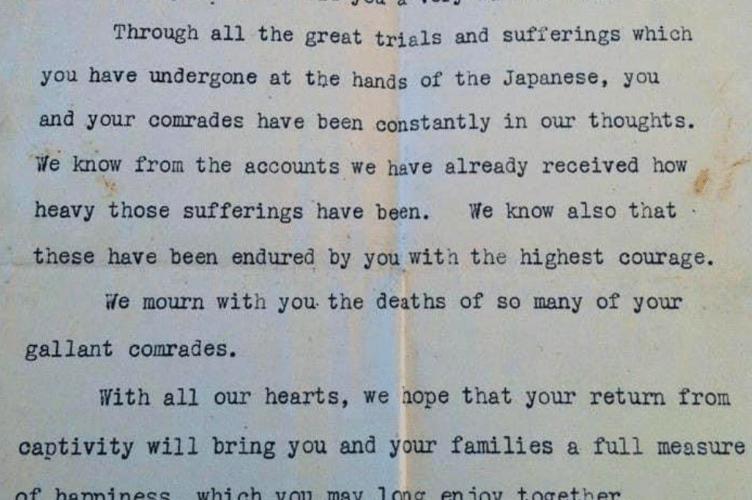

It's a time not only to honour the success of British campaigns in Burma and across the Far East, but also to reflect on the tens of thousands of servicemen captured by the Japanese—and their extraordinary bravery and resilience in the face of unimaginable hardship.

One of those was Leading Aircraftman Ashford Stanley Vaisey—known to most simply as Stan—who was born and raised in Alton.

His granddaughter, Shelley Vaisey, has carefully pieced together Stan’s wartime story, uncovering the harrowing experiences and acts of quiet heroism that defined his years of service.

Stan’s journey began in July 1940 at RAF Cardington, where he entered the telecommunications trade and trained as a radar operator—a role that would soon become crucial to the war effort. In an interview with the Soldiers of Oxfordshire Museum, he recalled those early days at RAF Yatesbury as “the back of beyond,” surrounded by mock radar stations concealed deep within the woods.

The training was rigorous and unforgettable. Stan described the Lister generators—“frightening things” that took four men to start—and the fragile copper-tube aerials held together “like a giant Meccano set.” These early challenges helped forge the resourceful spirit that would later carry him through far more severe trials.

After further training at the Bombing and Gunnery School on the Isle of Man, Stan began to grow restless. “We didn’t see any action… all the action was abroad,” he recalled. When a fellow airman asked to stay behind due to family concerns, Stan volunteered in his place: “I said, look, he don’t want to go. I’ll go.”

At just 20 years old, he boarded the troopship Empress of Australia as part of a convoy bound for the Far East, with Singapore as their destination—a key British stronghold in the early days of the Pacific War.

In late 1941, Singapore offered stark contrasts. Stan remembered the relative comfort of life there: “The life, the whole standard of living—you had servants to do this. You never cleaned your shoes. They were done for you. If you laid in bed, a bloke would come around with a bowl and shave you.”

But this brief idyll was not to last. “This soon changed.”

The Japanese invasion in February 1942 shattered any sense of security. Stan witnessed the bombing of Keppel Harbour and the fires at the oil depots, scenes he captured in photographs.

The retreat that followed was both chaotic and perilous. Stan described the desperate escape attempt by boat from Singapore to Sumatra, then onto Java, hoping to reach Australia. “The boat we got on got sunk… we found ourselves in the middle of a Jap convoy. Believe it or not, we were sailing along in the dark.”

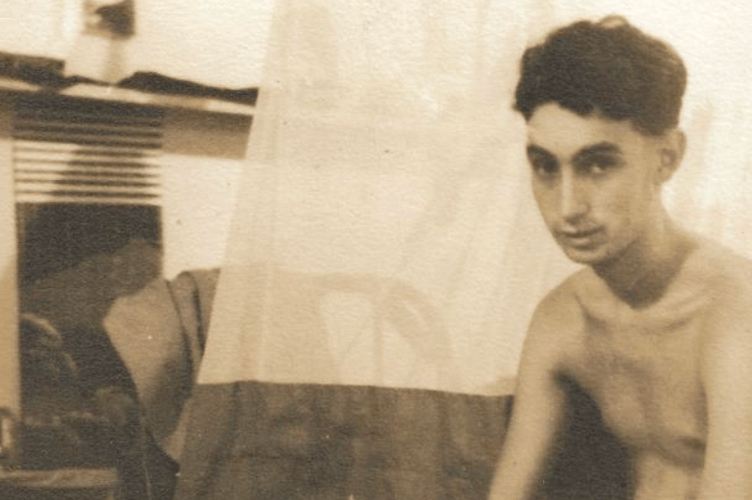

On March 17, 1942, Stan was captured in Sumatra after narrowly evading Japanese forces. What followed were three and a half brutal years in captivity, working on the notorious Thailand-Burma Railway. Starvation, disease, and hard labour became part of daily life.

Stan recalled those years with haunting clarity: “We ate ‘blue rice’—what they use for cow feed—and it was full of livestock, like weevils and bugs.”

Camps were spread roughly 20 miles apart, each worse than the last. Conditions deteriorated the further “up the line” they went, with food and medical supplies growing ever scarcer.

Despite the horror, Stan endured. He was moved between camps—Chungkai, Linson, Tha Muang, and Pratchai—doing whatever he could to survive. When stricken with diarrhea and malaria, he was transferred to hospital camps, which, while grim, offered a brief respite.

In 1945, liberation finally came. Stan was flown out by Dakota aircraft—an airlift that spared him days of agonizing travel. He returned through RAF reception centres established to care for returning Far East POWs, slowly recovering his strength.

Coming home to Alton felt surreal. “The station looked just the same. The same porter was stood on the bloody station.”

A kind neighbour, Martin, helped him home. “I knocked on the door. Aunt came to the door and she said, ‘Martin, who’s that?’ And she said, ‘Oh my God, is he all right?’”

Stan returned with a trunk of small treasures, such as tea, silk cloth, and other rare items. The tea astonished neighbours. Reverend Stringer, the local vicar, even brought over a box of oranges, once unimaginable luxuries during the war.

The medals he earned, the War Medal, the Pacific Star, the Defence Medal, and the 1939–1945 Star, silently testify to a remarkable story of survival and courage.

Yet through it all, Stan remained modest. “I was just doing my duty,” he said. But to those who know his story, that duty was anything but ordinary.

_-004.jpeg?width=209&height=140&crop=209:145,smart&quality=75)

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.