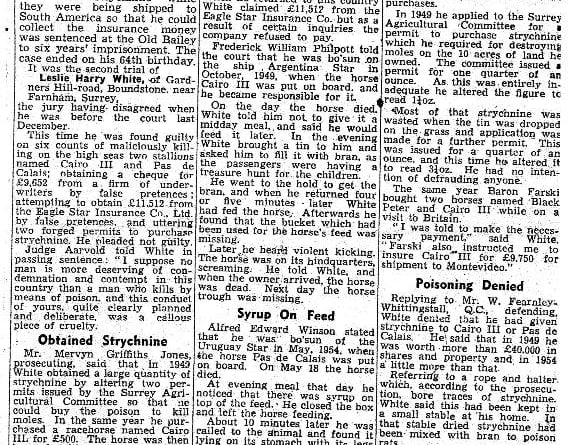

Nigel Parcell passed me an interesting snippet recently: “Going through some old papers I have come across an extract from an article in an unknown publication which dear old Brian Colley gave me shortly before he died and which I had forgotten about. I attach a copy of the article which I hope is readable. You will see it relates to a Leslie Harry White who lived in Gardeners Hill Road, Boundstone, and who was convicted of poisoning racehorses.”

But that was only the start of the trail as Nigel contacted Brian’s widow, Ros, and discovered more about Brian’s connection with the story. Mr Colley had been a merchant seaman and, it seems, had served on the vessel on which one of the incidents took place. Before his death he had started work on an autobiography and Mrs Colley has very kindly allowed me to reproduce a section here.

“A DEAD CERT,” writes Brian. “In May 1954, on my second trip, we loaded in London a rather splendid-looking racehorse. It was carefully lifted on board, complete with and inside a strong wooden horse box positioned on the well deck by No 6 Hatch and securely fastened down for the forthcoming journey to Santos.

“There was sufficient room for the horse to move about, but could not be allowed out of the box in case it took fright and tried to escape by leaving the ship mid-voyage.

“A Mr Leslie Harry White, a bloodstock dealer, travelled with us to tend the animal that became a centre of attraction for crew and passengers, standing with its head out of the barn door waiting for titbits.

“Our bosun, Alfred Edward Winson, took it upon himself to help the owner in every way possible, maintaining the welfare of the horse. After all it was insured for some £11,500, a considerable sum in 1954.

“Two days out from Las Palmas, May 18, Bosun Winson checked the horse, Pas de Calais, at evening meal. He noticed there was syrup mixed in with the food and left the horse feeding. Shortly after this, the bosun was called to the animal and found it lying on its stomach with legs askew, quite dead.

“Needless to say there was great concern aboard, disbelief that such a thing could have happened. The horse had appeared well, and showed no signs of illness.

“The ship’s doctor was summoned, the nearest person we had to a veterinary and certified the horse was dead. We could not keep the horse on board, nor could we turn round to take it back to port for a veterinary examination.

“Authority from London office was given to dispose of the unfortunate animal. Pas de Calais would soon ‘Pas over de side’. It was decided to wait until nightfall and with tarpaulins screening the area from the view of the passengers, the horse was given an unceremonial burial at sea.

“Bosun Winsun, with presence of mind, kept the horse’s feeding bucket, suspecting something was wrong and that the horse had eaten something bringing about its death.

“We later learned the dealer Leslie Harry White returned to England and tried to claim the insurance money. Eagle Star Insurance investigated the claim and White appeared for trial at the Old Bailey.

“With the help of evidence given by Bosun Winson and the traces of food in the bucket, the case of poisoning by strychnine was proved. On his 64th birthday, White was sentenced to imprisonment for six years.

“The case was well documented in the national press and it turned out that White, a bloodstock breeder from Farnham, had claimed insurance five years earlier for a similar incident while shipping another horse on the Brazil Star.

“The horses were being purchased for about £500 each and insured for about £11,000.

“Ironically, the day the horse died, we had a film show on deck for the passengers. The film, featuring Stanley Holloway and Joan Collins, was titled A Day to Remember.

“It certainly had been.”

Guy Singer took up the challenge to find a little more about the story and noticed a name which might be familiar to readers in the newspaper article – that of Fearnley-Whittingstall.

“QC William Arthur Fearnley-Whittingstall died young in 1959 – he was born only in 1903. Despite dying at a relatively young age he still managed to rise to being a QC.

“His father was Herbert Oakes FW. Hugh FW, the chef, born 1965, is the great-grandson of Herbert Oakes!

“Leslie White was tried twice for this in 1955-56. In the first trial the jury could not make a decision. After the second trial he was found guilty and sentenced to six years. The deaths of the two horses were five years apart. The first incident did not attract any controversy or any accusations.”

The last really emphasises the point that Brian made — always make sure you keep any evidence!