Imagine a sunny afternoon, a pretty country cottage bounded by green hills, a flower-filled garden complete with duck pond, and a wartime scientist who is absorbed in solving tricky mathematical problems while his understanding wife provides encouragement and regular comforting cups of tea. It sounds idyllic, and such a scene is depicted in the film The Dambusters, where inventor Barnes Wallis conducts experiments to test his (soon to become famous) bouncing bomb theory. It is of course a totally true story, but Wallis wasn’t the only one.

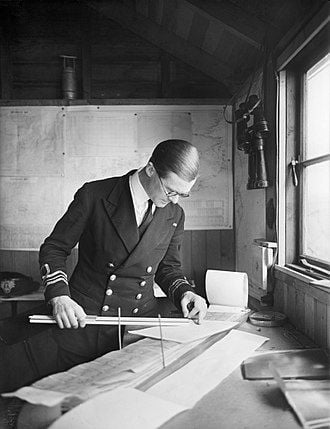

Wallis’s real-life house was in Effingham near Guildford, and not so many miles away, at the other end of the Surrey Hills, there was another cottage which could have easily fitted the same description. Situated in Haslemere, on the Liphook Road, just after Shottermill Ponds, it was named ‘Rats Castle’, and since 1939 it was the home of one of his colleagues, Robert Lochner, a scientist, engineer and mathematician. In fact, they were also good friends and Wallis was a frequent visitor to Rats Castle. They had much in common. Both had a naval background and both had to give up active service through poor eyesight and thankfully for this country, they instead concentrated on research and invention. They equally bore all the hallmarks of genius; fiendishly clever, delightfully eccentric, an unshakeable belief in their work, and a dogged determination to overcome all obstacles placed in their way.

Both men were recruited into the Admiralty’s Department of Miscellaneous Weapons Development (DMWD for short), swiftly corrupted by some wag as “The Department of Mad Wheezes and Dodges”, a nickname that would stick throughout the war! Its team of scientists became colloquially known as the Wheezers and Dodgers. It did not take Robert Lochner long to make his mark in the department. The Admiralty was seriously concerned by the threat from Germany's magnetic mines, which did not attach to ships' hulls as might be imagined, but instead detected the metal of their structure. As a ship passed over one of these mines, the magnetic fields inside were disrupted, triggering a fuze which detonated the charge.

Lochner was assigned to solve the problem, and together with a team of scientists, he came up with the degaussing girdle, a skirt of copper cables fitted around the hulls of ships, which when energised by a special electric current, neutralised the magnetic field of the ship and eliminated the threat from these mines, thus securing the future of the north Atlantic convoys that were vital to Britain's survival.

In the Spring of 1943, around the time when Barnes Wallis’s bouncing bombs were about to fulfil their true potential, Robert Lochner experienced a phenomenon of which all inventors dream…

A Eureka moment. A scientific breakthrough; the realisation that the solution to an ongoing problem has been accidentally stumbled upon, and this particular moment would set him on the path to great recognition, and a place in history.

“Eureka” is of course eternally associated with the father of inventors, the Ancient Greek mathematician Archimedes, who as every school-kid knows, observed upon getting in his bath, that his body displaced the water level, and so he immediately jumped out again, and ran naked through the streets of Syracuse, excitedly shouting out the immortal term, which translates to: “I’ve found it!” By pure chance he had discovered how to measure relative density. For Lochner, it also came by pure chance while having a bath, as he idly played with his face flannel. It was the old-fashioned type, made in the shape of a bag. Filling it with water to give it some weight, he held the top part on the surface, rippling the water on one side. The water on the other side remained still and at that moment he knew he was on to something.

It is a rather lovely poetic coincidence that Robert Lochner’s Eureka moment should, like that of Archimedes, have come to him in the bath, and that he leapt out and actually shouted out the very word, but, fortunately for his wife Mary and his neighbours, he didn’t run naked through the streets of Haslemere to declare it. Instead, he quickly got dressed, and with Mary, rushed to an out-house where there was an old Lilo. They folded it to make a tube shape, attaching an iron pipe as a keel. With this and a handy cricket bat, they rushed down the lawn to the pond and floated the Lilo, making waves with the bat. The effect was exactly the same; still waters. He realised that it was because wave turbulence only went to a shallow depth. His excitement was every bit as intense as that of Archimedes, because Lochner was working to a personal request from Winston Churchill.

The story goes back to early 1942. As soon as the United States of America joined the war, plans began to be drawn up for the Invasion of occupied France. Two things were clear from the outset. Firstly, to secure and reinforce a firm beach head, a harbour was necessary to ensure rapid deployment of supplies and men, and secondly, as the Dieppe raid later proved, ready-made well-defended harbours were very costly to capture. Therefore, a portable floating harbour system was envisaged, one that could be taken to the landing sites in sections and assembled in short order. This idea evolved into what became the Mulberry Harbours, which were made of concrete and could be towed across the English Channel to the invasion beaches. Two were required; one for the Americans and the other for the British and Canadians. There was one problem to be solved; the power of the sea. Most permanent harbours have sea walls to protect them from rough seas, but these portable harbours would be exposed and extremely vulnerable. “Calm the waves!” was the stark and simple instruction to Lochner from Churchill.

The layman could be forgiven for assuming that the story goes straight from the flannel and the Lilo tests to full-sized floating breakwaters and natural success. Nothing could be further from the truth. As Barnes Wallis found out, it’s one thing to conduct positive exciting experiments in your garden, but quite another proving your theory works when it is scaled up for the real thing, and so it was for Robert Lochner too.

As well as being a scientist, he was a very experienced sailor, and thus well versed in wave dynamics, which was just as well, since for his calculations he had to wade through a plethora of complex equations and formulae that might have given even Einstein a headache! The task was to work out the exact size, shape and construction of a floating breakwater, tailor-made for the sea conditions in the area of the invasion beaches, and guaranteed to withstand the worst possible storm conditions expected during the period it was to be in place. This was agreed by the weather experts to be Gale Force 6.

How Lochner set about his task is a story in itself; an entire book in fact. It is suffice to say for this account, that he and his team wasted no time and excelled themselves. The first working model of a floating breakwater was constructed in the weeks following his Eureka moment. He was well into designing and building full-scale breakwaters when he was summoned to the Quebec Conference in August, where it was decided that D-Day would be scheduled for early May 1944.

Not long after his return to Britain, on the 4th of September, he was contacted by President Roosevelt personally, who told him that his ‘Bombardon’ floating breakwaters needed to be ready and in place by May the following year, giving him a mere eight months! In December, the date was revised to early June, but it was still a tight schedule. It is testament to his skill and dedication that during this period the remainder of the theory had still to be formulated, over three hundred model-tests had still to be made, the full-scale designs and production plans had to be prepared and over 4 miles of an entirely new, and as yet, untried form of floating breakwater had to be built, assembled, tested, and then finally towed 100 miles from the English coast and laid out under the fire of German guns. That it was completed and ready to move off with the rest of the invasion fleet is a remarkable tribute to all who took part in this great enterprise.

The floating breakwaters were completed and protecting both Mulberry harbours by D-day +6. Readings then showed that with a wind strength of Force 5, outside the breakwater the height of the waves was about seven feet, but inside the breakwater, the maximum height of sea was less than 18 inches. Robert Lochner’s calculations were spot on. He had delivered on his promise to Churchill; he had calmed the waves!

On the 19th of June, the worst gale experienced in the English Channel in June for over 40 years blew up. During the 4 days from the 19th to the 23rd, seas over 15 feet high and 300 feet long drove in on the two Mulberries. The stresses generated by those great waves were more than eight times those with which the harbour components were originally designed to compete. The Bombardons at both harbours withstood about 30 hours of this gale before serious damage occurred.

On the 23rd of July, Churchill visited the harbours, and on his return stated: "This miraculous port has played and will continue to play a most important part in the liberation of Europe". As a reward for his war efforts contributing to the Mulberry harbours, Lochner received the (then) remarkable sum of £5,000 and later was awarded the MBE.

Rats Castle still exists. A blue plaque denoting Lochner’s achievement is mounted on the cottage and was presented by English Heritage and The Haslemere Society. His daughter Adrianne lived there until 2022 and now lives in nearby Liphook.

Mick Bradford 2024

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.